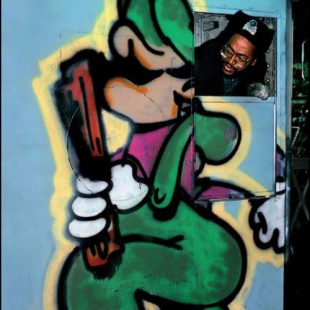

“This boy,” says legendary photographer Martha Cooper, pointing at an image of a teenager in her new book, Street Play, “this is the connecting point between Street Play and graffiti.” Cooper has just highlighted the exact moment which first sparked her interest in graffiti and led her on a notorious journey documenting the NYC subway graffiti culture and its major writers.

It culminated in the release of her seminal graffiti book, Subway Art (co-authored by Henry Chalfont) which catapulted the movement to mass audiences worldwide.

It culminated in the release of her seminal graffiti book, Subway Art (co-authored by Henry Chalfont) which catapulted the movement to mass audiences worldwide.

This chance meeting with a young graffiti writer known as HE3, occurred during a personal project undertaken by Cooper in the ’70s which involved taking images of children at play in Lower Manhattan’s Alphabet City. For the New York Post photojournalist, this was a ‘hobby’, just something she did to fill the time on her way back to the office. At a time when NYC was facing imminent bankruptcy, and buildings were being torn down, derelict neighbourhoods like Alphabet City provided the perfect backdrop for a children’s playground.

To Cooper, a former anthropology student, the kids’ creative use of raw materials and vacant lots in their poverty-stricken surroundings, was both intriguing and captivating. While she built up a significant body of works around this subject matter, her newfound—and more pressing—interest in graffiti took her on a different path and it is only now that she has decided to release these early images of Alphabet City’s street kids. Produced in association with Eastpak, Street Play is a compelling collection of images that once again demonstrates Cooper’s mastery at unearthing and capturing rare subject matter and turning it into cultural artefact.

It was HE3 who first encouraged Cooper to photograph the city’s graffiti. Cooper explains: “He said, ‘why don’t you take pictures of graffiti?’ and he explained that that was his name and he was putting it on walls. And that was the first time I understood that: one, they designed it first; and two, that it was his name. I didn’t realise it was his name or that any of these things were names. In fact, what I had seen of graffiti always was a little frustrating because even if you could read it, it didn’t ever say anything. And then as soon as he explained it was his name, it made perfect sense.

“HE3 introduced me to Dondi who was a king of the line. When I first met Dondi, his sketchbook where he designed his pieces, on the very first page of that book, just happened to have a picture that had been published in the New York Post that had a Dondi tag in the background…and it had my credit on it. So when I met him he was ‘aah, you’re Martha Cooper’ and he opened his book and showed me the picture I had taken. So that was like an instant connection.”

Although Martha Cooper and Henry Chalfont (the two most renowned chroniclers of graffiti) released Subway Art together, it was competitive between them in the early days. But after they both failed to get their own books published, they made one of the most important unions in the history of graffiti photography and decided to combine their works: “We just figured there couldn’t be more than one book and maybe that if we just put them together we’d have a better chance,” she says.

Over 20 years after its original release, Subway Art is still hailed as the ‘graffiti bible’, but back then, the pair struggled to find a publishing house that would take the subject matter seriously enough to see its potential. Cooper explains: “Everybody hated graffiti so much. They saw it as a plague…We couldn’t get it published in the States. It was published by Thames & Hudson in London.

Over 20 years after its original release, Subway Art is still hailed as the ‘graffiti bible’, but back then, the pair struggled to find a publishing house that would take the subject matter seriously enough to see its potential. Cooper explains: “Everybody hated graffiti so much. They saw it as a plague…We couldn’t get it published in the States. It was published by Thames & Hudson in London.

“The way we got it published, we went to the Frankfurt Book Fair. We had this big proposal that we had to wheel around and went to publisher after publisher and Thames & Hudson finally said they would do it, after maybe 25 other publishers rejected it…. In fact, I think Thames & Hudson got a lot of slack from other publishers saying, ‘look what you’ve gone and done now, spread this vandalism around the world’.

But now Thames & Hudson has a whole series of street art related books. I think it’s probably become their most major seller.”

Cooper is still in touch with HE3, who “resurfaced when the Hip-Hop Files came out because we used the same [Street Play] photo. He had been in prison for 15 years. He’s an adult now. He’s out. He doesn’t really have a job which is kind of sad, but I am in touch with him.”

This photo of HE3 should act as a historical landmark. It is the beginning of the Subway Art story — a book which has acted as a catalyst for the global street art movement and inspired thousands of young artists all over the world.